#48 Grieving, a year later

How can we stop any of it?

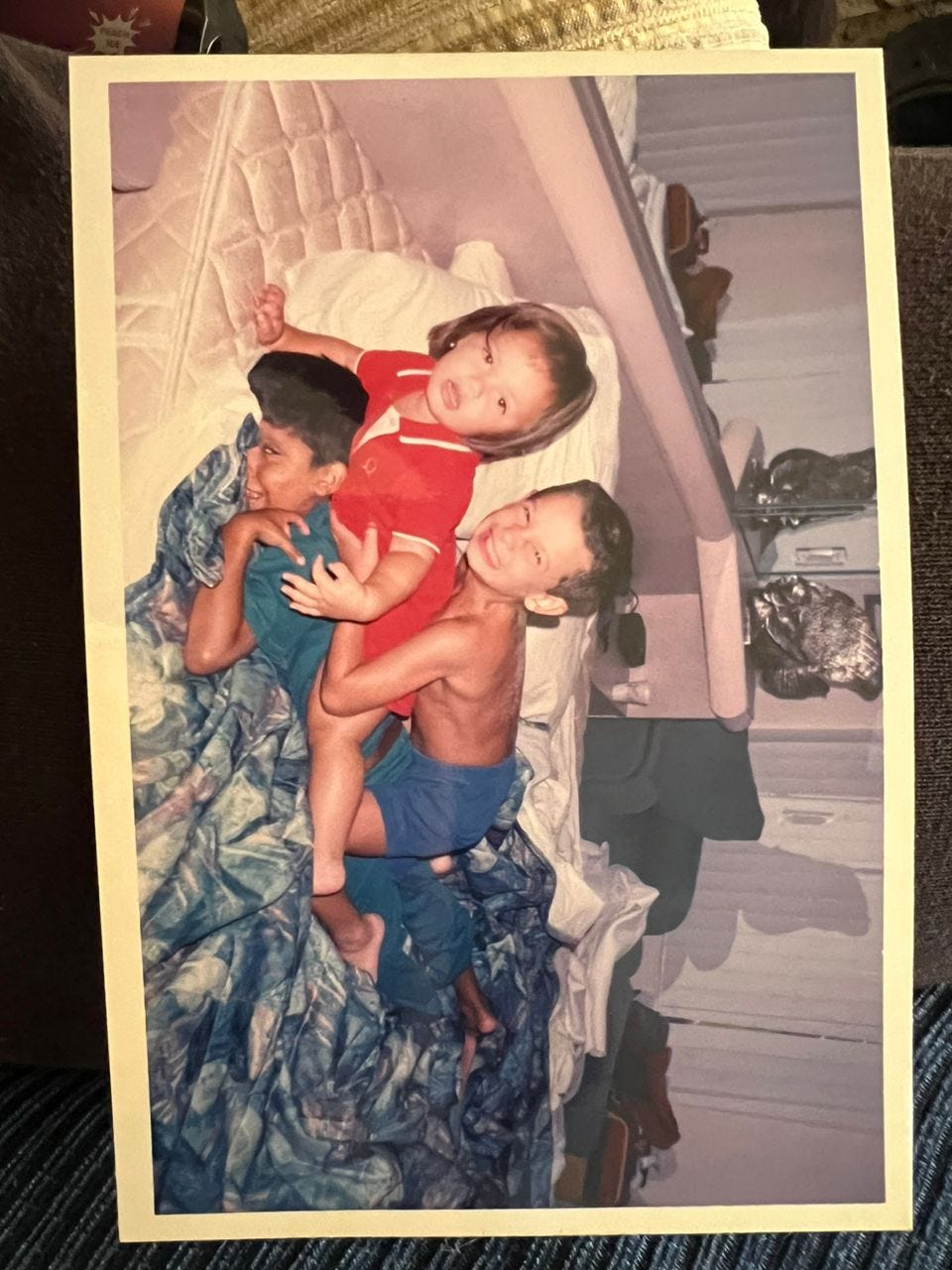

In twelve days it'll have been a year since my cousin died, and I think we are all unprepared for marking the date itself. I am already dreading the crying and the memory of my dad, stifling his sobs over the phone when he told me he died. Across a few countries, he was at sea at the coast of Spain when he heard the news and I was in the kitchen, preparing slides for students, meant to happen that afternoon. I remember the crack in my chest – I remember asking my cousin to let me know he was doing okay.

Then I dreamed a recurring dream ever since my grandpa died in 2018 – he is sitting at the airport's departure hall in the capital, waving goodbye, his walker stick on his other hand, made of dark shiny wood. But then a new figure was next to him, wearing a flannel shirt and dark blue jeans, his square black glasses, drinking whiskey on ice. They were together now, waving me goodbye at the airport.

My cousin never waved me goodbye at the airport in this life, he would hug me days prior to my departure every time I went back to the Netherlands. I was lucky in having been able to go three times the past two years, for a month or more at a time, bridging gaps and closing all this time between us. We spent new year's eve together in December and we toasted at midnight, he had told me he was dating someone and his eyes sparkled, when I asked him if he loved her (he did). He nodded sheepishly and with a tinge of self consciousness (even though he was an Adult in his 30s and we're meant to Act Normal). I loved that about him. His sentimentality. The men in my family have always been romantics, sentimental guys with a smile. Not a single one of them was ever grumpy.

How do we stop time? How do we stop these things from happening? The people we love, the friends we have, we always think we have more time. I thought I had more time.

I spent my birthday at home for the first time in eight years, and I got ready in my childhood bedroom and my aunt came to visit and we sat there together, in the same spot he used to sit with us at. My oldest sister called him on the phone later that night to say hello, to his voicemail. What can you do? How do we stop it? Her 36th birthday was two days ago and her cake said, "Elías & Michelle forever" and I cried. She last saw him a year earlier, on her 35th birthday. You always think you have time.

Most days nowadays are easier. There are lapses of time in which everything is exactly as it was. I have the privilege to have built an everyday life that doesn't feel his absence of the past eight years but now I wonder what it would be like if I had. I think about whether he would've gotten married if he'd still be alive today. Or had any kids. Or got to visit me here, across the world. In my mind's eye I think of how weird it sounds to think I can't talk to him anymore.

I left Venezuela sometime in late January in 2022, thinking I would have time to catch up with him later. Our last messages were about going to the pool and sunbathing and swimming; but I didn't have the time. I promised I'd see him next time. We didn't get to say goodbye and it's something I think about often. You thinking you have time is a necessary illusion to have. You can't live thinking of all the last times you'll do something or see someone – life becomes cruel, untenable, unsustainable. A fearful, tiny thing, sucking the joy out of everything.

Grief is very strange. My grandfather is in videos, telling me how happy he is for me to live abroad and to go to school and that he can't wait for my final results and come to my graduation. The day I got my results was the night he died. I like to think he was waiting to see what I'd score and as I went into the office that day with cake, I saw the messages at 11 am my time. I went home and cried.

All these things become so insignificant, don't they? These little things that become so small but mark the trajectory of a day, mark a moment in your life. The odds are not in our favor; it is certain that we won't last forever. Maybe in the future they'll make a machine or a faraway phone, a landline to connect to, to ask if they're okay. The urge to connect to something bigger than yourself comes in those moments. The agnosticism of your teens becomes your spirituality in your twenties. I find agnostics and atheists brave nowadays. Untenable and untied to anything, dust becomes dust! Nothing more!

And I ring and ring and ring the landline in my dreams; I ask my abuelo and Elias for guidance; they tell me to just hang in there, better things are ahead. They tell me to be patient in their good-natured way. I tell them okay, I will wait. I tell them to show me later on that they're okay.