#3 Everything is information

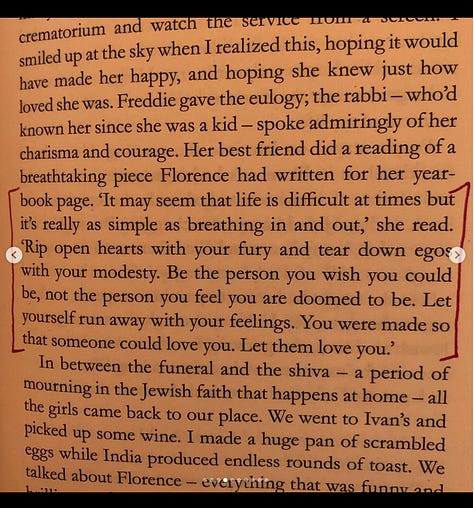

about being who we want to be, not who we feel we're doomed to be

Mid-January and the weather's pretty from this side of the world. I'm flying back to the Netherlands next week, and I'm feeling a jittery sense of excitement to hug my friends again, go to the cinema, take long walks and visit my favorite coffee place. I brought my dad a can full of their winter special blend, which he subsequently called “fucking strong coffee” without knowing that was the label. We have coffee every morning, the last weeks seeing me arriving once he's had the last sip, foamed milk clinging to the bottom of his cup. While I'm writing this, my dad is sitting next to me, cleaning up his portable radio from a day spent at the beach. Sand collects in the crevices and he devotedly wipes every part clean. The sea is in front of me, shimmering and reflecting the glare of the Sun at midday.

Last week I was writing about how I'm trying to unravel a mixed sense of identity, something I'm sure many people who immigrate feel at several points of the process of making a new place home. The past days, I've been wrapped up in a lot of feelings about what it means to be part of a family, to belong, and what it can all teach us about how we understand love. Especially how we understand ourselves, and the way we see the world around us.

I've been especially attentive to all these things since I first started watching Another Self, a Turkish Netflix series. The three women, friends for many years, find themselves in Ayvalik, embarking on a spiritual journey to understand their family's history and trauma, exploring ancestral wounds, and healing their own in the process. I've been writing every morning (following the Morning Pages practice, something I think everyone should try, regardless of considering themselves a writer or not), and, during one particularly clear morning, I wrote about how when it comes to family and discovering a sense of self, everything is information.

To me, coming home is the act of spending time with family. Parents, grandparents, cousins, siblings. So, regardless of whether I spend time with them in another country or in the city we're from, home is deeply intertwined with family for me. It's a deep, long-running stream of information: about who I've been, where I come from, but also where I first processed a way of seeing the world, information that I distilled, analyzed and carried with me into my relationships outside of the family.

Coming home is about distilling information. Everything that happens there is information —deeply valuable, ready to be sifted through, analyzed and understood —it is the kind of information, too, that is only accessible when we're with the people who raised us. It's an unnerving process, because a lot of it can make us feel vulnerable. Sometimes, even anger can come up as a result.

I spent the first weeks of my visit being really, really pissed off. I was angry about many different things, but mainly about how I was expected to sacrifice more of me, to give up more of my time, and the resistance I was met with when I continuously said no. The frustration reached a peak when I heard my aunt say that I was simply too loved, so deeply loved, and that's why my resistance was met with so much pain, so much sadness.

The truth is that there's a lot of information in that one sentence. A lot of things crystalized the first days of January: one of the most important findings I made was understanding how my family expresses and appreciates love. Combined with trying to trace back where these information pieces first came from, I saw something I had overlooked (or just never really distilled): love was being associated to possession. To a lack of boundaries, from time and space, to be enmeshed, to spend time with the person you love because it is your duty, because you have to.

After about eight years away from home, it's not really surprising that my own ideas of love have taken their own shape. I've had a chance to build my own relationships, to choose what works for me, to decide. In a family context the entire game is different. You're born into a play mid-performance. Roles have been chosen, dynamics have been built, and history's been made. You're a vessel for a familial body, and the beliefs they've developed over the years. I've learned that to ignore your history is to ignore yourself.

By understanding how generations before me have loved, I've understood where my own impulses come from. I can become overbearing, I can be intense, I can feel insecure of other relationships the people I love have, even jealous. I can feel hurt by something as seemingly innocent as someone forgetting to pick up my call or reply to a text, and I still struggle a tiny bit if someone I love forgets my birthday. These are all things I grapple with that I didn't even know were there most of the time. It's just always been that way.

There's a lot of information about how to love in the world: grand gestures, commitment, jealousy, possession; the warnings of a love misdirected, the inherent attachment of loving someone and the vulnerability that represents. There's even more information within our own families about what love means. How do your parents love each other? And if they no longer do, what was the first memory you have of someone showing care in your family? How do your grandparents love you? Do you feel loved by the people you love?

Nowadays is also filled with information about attachment styles and love languages and self-help books describing how we should love, what we should do. But I've noticed that all these measurements and examinations on love skip on a really important source of information, perhaps the most important one —but also sometimes the most painful to look at— our own ancestry. The ways love has bound us and the ways it can dissolve us. Whether we choose to or not, we're born into a long history of repeated actions, familial patterns, and sometimes they're motivated by things we don’t immediately recognize as harmful or unhealthy. What is there to compare to? Without the space I've had from home in the past eight years, would I know how to distinguish it?

In the same vein, I've thought about how feelings are information. My anger in December was information itself. Anger is a powerful thing: I read somewhere that it's important because it tells you when you've been disrespected. I think anger also rarely shows up on its own. For me, a lot of the anger that came this time was intertwined with sadness, and with anger directed at myself. I wasn't struggling anymore with laying down a limit, with saying no, but I was struggling with everything that came after. It wasn't until my aunt said I was deeply loved as a response to my frustrations for lack of space that I understood how people around me perceived love. It wasn't only her; my eldest sister, my mom, my dad. They all implicitly agreed that love was something demanding, something that needed your time, that didn't care whether you needed space, that needed a response. Love was something that had to be devoted, taken, and didn't care whether it was giving in return. If the question was to ask for space, the answer was that you must not feel that love at all. Otherwise you'd gladly give it up.

When I've been territorial, when I've been hurt by a lack of response, when I've taken offense with anything other than immediate availability, I've been reading from the same script I learned growing up. And yet I don't feel doomed to be this person, someone who demands to be loved at any cost, simply because they love in that way. I've seen ways that I've loved become beautiful testaments to my relationships. I've loved with unquestionable loyalty. I've loved with longevity, without asking much more other than to be around the people I love. I've also loved from a distance, and learned that my feelings are just that —my own information, telling me what I care for— without having to direct them, share them, do anything about them. Being who I want to be has had a lot to do with learning who that is in the first place, and how much of that is who I already am.

I credit much of the loyalty with which I love with to my family too. In a Venezuelan context, family encompasses everyone. It was really weird to be in the Netherlands and realize most peers visit their grandparents every few months, maybe once a month if at that. Our family visits each other often. We celebrate birthdays with aunts and uncles, ring in the new year with cousins, spend days in the sun with each other. Most of my family lives in the same city they grew up in, a short car ride from each other. Love is in the way my aunt makes her mother coffee every day, visits her in the afternoons. Love is in my mom's daily texts, asking how I slept. Love is in the car rides I make to the next city over to spend the weekend with my cousin. Love is in his wife's conversations with me, how she makes me breakfast.

Everything is information —how we love, how we experience life, how we make sense of how we feel— and sometimes that information is confronting. It certainly has been for me. So much of what love is, is inherited. So much of what we see growing up across generations is what we learn to give. To ignore that information —to grow away from it, to ignore it— is to ignore where we come from. History doesn't start with your mother, doesn't start with how your parents met. And there are pieces of information that you'll never recover; lost to time, lost to life, lost in the way that great-grandparents’ parent's name are forgotten if they're not recorded. I think the error isn't in not remembering it; it's in not acknowledging its importance in the first place.

Family is one of the greatest, most confronting sources of information we'll ever sift through. To see it, and to try to understand it, it is to decide who we've been, but also who we want to be.